In reading essays on Master Hua’s life, I came across this quote:

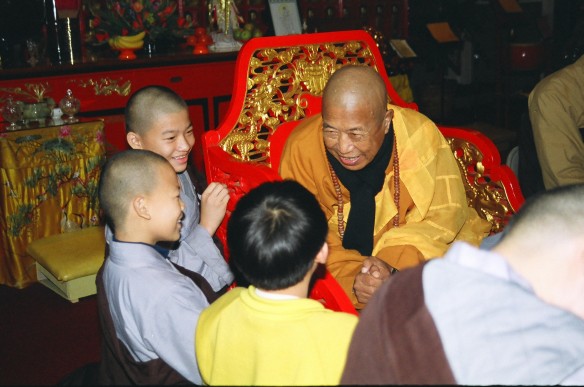

“The Master was always open, direct, and totally honest with everyone in every situation. He treated everyone equally, from the President of the United States to little children.”

It makes me reflect: Am I honest? Do I say what I mean? Well, I try. Yet, I often notice how strands of my ego color and shade the meanings and intentions behind my words.

It made me smile. Mainly because that type of direct, open honesty can be hard to come by these days. It makes me reflect: Am I honest? Do I say what I mean? Well, I try. Yet, I often notice how strands of my ego color and shade the meanings and intentions behind my words. My limited worldview, or my own insecurities, fears, and doubts, can cause me to over or under-compensate my speech and acts so that they will come across in the way I want. Already, this type of thinking is a kind of performance. I am composing and filtering my thoughts and acts to create an image of who I want to be. Why? Because of thoughts like, “I want this person to like me,” or “I don’t want to sound like I don’t know what I’m talking about,” or “I don’t know what I’m talking about.”

Sometimes, it’s important to pay attention to our audience—to think through what we’re going to say or how we’re going to act so that we can meet others where they are. It’s helpful, so that we can connect on the same page, speak in the language of those who are listening. But to what extent is it too much? How can we reach a level of discernment where we can carry that childlike honesty with us through the complex web of social structures and conditioning? How can we talk to rather than at each other?

Recently, I picked up a book called Insights: The Wisdom and Compassion of a Buddhist Master¹. It’s a collection of quotes from questions and answers between Master Hua and monks, nuns, disciples and people from all over the world. The tone of the dialogues really reflect the direct honesty and lighthearted openness with which he seems to have carried himself.

Here are some that stand out:

Q: May I ask how my future will turn out?

A: Ask yourself whether you’re compassionate. There’s no need to inquire about your future. (81)“Anything that we’re attached to becomes a burden to us.” (103)

“Everything is a test to see what you will do, what I will do, and what he will do. If we don’t recognize what is before us, we must start anew. We must truly recognize our faults in each difficult situation. Do not criticize others. If we really know our mistakes, we don’t need to worry about whether other people are right or wrong. Others’ faults are simply my own; knowing that we are all the same is great compassion. Be extremely kind to those with whom you have no affinities. Great compassion is to understand that we are all the same. By being kind and compassionate to people, we will have no more problems.” (103)

Q: Uh oh, so-and-so is leaving, who is going to be translating in the future?

A: No one is indispensable. It’s never the case that only one person can do something. (67)A sincere Catholic didn’t know what to do when he first stepped into the Buddha Hall as a guest. Suddenly the Venerable Master appeared and said with much kindness: “Just treat this like your home. Do what you think is right. Don’t worry.” The guest became relaxed. (37)

¹ Venerable Master Hsuan Hua. Eds. Bhikshuni Jin Rou Shi, Bill and Maureen Dorey. Insights: The Wisdom and Compassion of a Buddhist Master. Ukiah: Buddhist Text Translation Society, 2008.