[This is the fourth of a series of posts reflecting on how I found myself drawn to monasticism despite (or perhaps because of) my upbringing in the Bay Area and providing insight into how the relatively secular environment in which I grew up prompted me to look deeper into the meaning of life.]

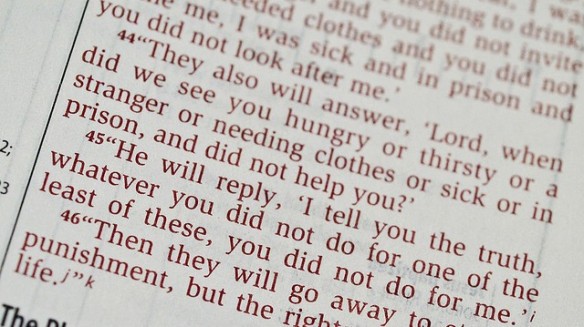

As I was diving into the depths of the wisdom of the various religious traditions, I still had these burning questions in my heart: “What do I believe?” “What path am I supposed to follow?” And, I couldn’t help but feel torn. I found the Biblical teachings of Jesus extremely inspiring and skillful. Especially skillful, I thought, was the way he dealt with the Pharisees when they brought him an adulterer for judgment. They were testing him because Jewish law mandated death by stoning, which violated Roman law. He responded with the often-quoted words: “Let any one of you who is without sin be the first to throw a stone at her (John 8:7, NIV).” At this point, the Pharisees left one by one, leaving Jesus alone with the woman. He then told her that he didn’t condemn her and that she should mend her ways.

… it is, for me, a clear demonstration of the principles of forgiveness and compassion.

This story, like many others in the Bible, demonstrates the compassion and wisdom at the heart of the Christian tradition. It is also a source of debate among scholars, who have found that it is not contained in early manuscripts of the Bible. Regardless of its historicity, it is, for me, a clear demonstration of the principles of forgiveness and compassion. When I was reading the Bible, I had a sincere group of Christian friends who were quite honest with me about their lives and religious experiences and to whom I could definitely relate a lot more than than to the prevailing materialism of society.

At the same time, I was studying Buddhism; and here, I also found teachings that rang true– teachings about how we should understand suffering and, more importantly, how we could transcend it altogether. Even growing up in the Bay Area, I could see a lot of suffering around me–not the acute pain of hunger or poverty, but rather, the pain born of the sense of meaninglessness that comes from having “too much.” I observed how Silicon Valley created conditions that led to family conflict. Both parents worked to pay the mortgage on the house (and all the material items our consumer society convinces us to buy), and as a result children come back from school to empty homes. TV and video games (and now Facebook, which didn’t yet exist) became like “substitute parents.” This, I saw, was the cause of the communication gaps and the misunderstandings that arose between the two generations.

Buddhism systematically demonstrates the “cause-and-effect” relationships around us whose ultimate result is suffering–a suffering we can transcend by living a virtuous life and by developing a deeper understanding of how things work through meditation practice. When I first encountered these ideas, they made sense to me; and the more I meditated, the more clearly I saw things and the more balanced and grounded I felt.

But at this time I also felt some internal tension, because I knew that my Christian friends were hoping I would make a “leap of faith.” Somehow, I was unable to do this, although I tried pretty hard. I could accept the idea that people who believed sincerely in Jesus would be saved and go to Heaven, but I couldn’t understand why everyone who didn’t believe should be destined to eternal damnation. What about all the good people in the world who weren’t believers? Although I felt emotionally drawn to Christianity, I found myself leaning more toward the Buddhist approach to the world.

But at this time I also felt some internal tension, because I knew that my Christian friends were hoping I would make a “leap of faith.” Somehow, I was unable to do this, although I tried pretty hard. I could accept the idea that people who believed sincerely in Jesus would be saved and go to Heaven, but I couldn’t understand why everyone who didn’t believe should be destined to eternal damnation. What about all the good people in the world who weren’t believers? Although I felt emotionally drawn to Christianity, I found myself leaning more toward the Buddhist approach to the world.

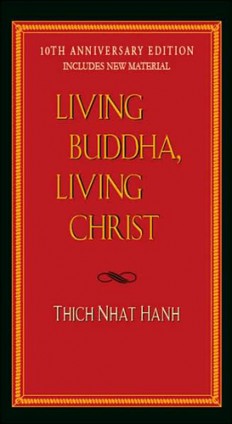

Hence, I decided that the only logical thing to do was to start at the place where both religions were in agreement: a humble heart, selfless service, unconditional love and understanding, and letting go of the endless desires of society. In fact, it was in Thich Nhat Hanh’s book Living Buddha, Living Christ that I first found out about Thomas Merton–a Catholic monk, but one who was open to Eastern spirituality. My idea was that if I started at the place where the two traditions overlapped, I would ultimately find out what path I was meant to follow.