We just published the 2011 Fall Course Catalog for Dharma Realm Buddhist University (DRBU). Check it out!

SHARE

SHARE EMAIL

EMAIL COMMENT2 comments

COMMENT2 comments

We just published the 2011 Fall Course Catalog for Dharma Realm Buddhist University (DRBU). Check it out!

SHARE

SHARE EMAIL

EMAIL COMMENT2 comments

COMMENT2 comments

I was chatting with another layperson… asking him what this particular lunar holiday would be in his tradition.

Between the program’s presentations, I was chatting with another layperson about the full moon, asking him what this particular lunar holiday would be in his tradition. He answered that they would be observing Esala Dhamma, the celebration of the coming of the Dhamma (Sanskrit: Dharma) into the world, on the day of the Buddha’s first sermon to his disciples twenty-five hundred years ago. Then he asked me if we also observe the same holiday at CTTB.

I shook my head and looked down thoughtfully. “No,” I said, “That holiday wouldn’t really have the same significance in our tradition.” This seems like a simple enough topic, but reflecting on it, I started my way down an interesting train of thought. When did the Dharma actually come into the world? The question itself is inextricably woven into our interpretation of cosmology and history; how we interpret it depends on our historical worldview and its scope in time and space. This question, perhaps timeless, is no less nuanced in the modern age than it has been throughout Buddhist history. Read More …

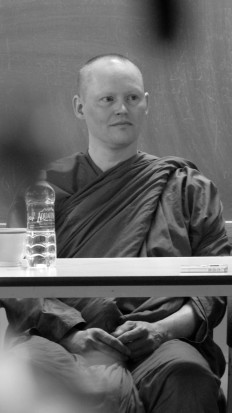

Ajahn Jotipalo

As part of the University’s Monastic Immersion Program this Summer, monks and nuns from different Buddhist traditions gave talks as guest speakers on topics ranging from the basic features of the Buddhism they understand and practice, the common spiritual exercises in their traditions, why they chose to “go forth” and enter the monastic order, and what attracted them to their particular traditions.

One of these guests was Ajahn Jotipalo. He is one of four monks from Abhayagiri Monastery in Redwood Valley, California, about twenty minutes’ drive north from the DRBU campus in Ukiah. In the evening of their day of the program, these monks—Ajahn Pasanno, the abbot of Abhayagiri Monastery, Ajahn Jotipalo, Kassapo Bhikkhu, and Sāmanera Suddhāso—took turns talking about how they entered the monastic life. They also answered questions from the students on a variety of subjects. Ajahn Jotipalo’s story struck a chord with me.

Already frustrated with having to clean a small space with nine other people, he all of a sudden found himself craving for a donut.

Ajahn Jotilpalo, who is from Indiana and has been a monk for more than 10 years, told the students what led him to Buddhism, and the experiences he had when he and a lay supporter wandered north along Highway 61 from New Orleans. However, it was his reflection on a seemingly mundane matter that stuck with me. In answering the question, “What’s the most difficult part of the monastic training?” Ajahn Jotipalo related a realization he had while cleaning the kitchen stove one afternoon. Already frustrated with having to clean a small space with nine other people, he all of a sudden found himself craving for a donut. Read More …

My friends and I, it seems, represent a trend that has recently been receiving a fair amount of attention. By the standards of the past, we are taking our sweet time settling down into a traditional adulthood based around marriage, family, and a stable career. Research points to a variety of sociological and economic explanations for the hold-up. One of the more in-depth reports was published in the New York Times Magazine last year. Titled “What Is It About Twenty-Somethings?”, this article suggests cause for concern, summing up the situation as follows:

The traditional cycle seems to have gone off course, as young people remain un-tethered to romantic partners or to permanent homes, going back to school for lack of better options, traveling, avoiding commitments, competing ferociously for unpaid internships or temporary (and often grueling) Teach for America jobs, forestalling the beginning of adult life. Read More …

We added another video on the Zen Chan Buddhist Catholic Dialogue, which took place at the City of Ten Thousand Buddhas. It is a short video conversation, featuring Sister Mary Ann Donovan and Professor Ronald Epstein.

For further info and full listing of videos on the dialogue, please visit this page.

The Monastic Immersion program has just kicked off with last Tuesday night’s orientation.

The idea of the program is to learn Buddhism by living and practicing in a Monastery and maintaining the monastic schedule. Thirty participants from a wide spectrum of religious and educational backgrounds will come to CTTB to participate in the program for ten days. I’ll be there for every section of the program, taking a break from my regular schedule to commit every moment of the day to the session.

We’ll be reading passages from various works on monasticism and its relationship to society in a variety of world cultures, going into more depth specifically in the history of the Buddhist tradition. We’ll also be studying a variety of Buddhist rituals and practices related to diversity of monastic life within Buddhism, while also engaging in them experientially during the intense daily schedule. Read More …

Gilles Deleuze (1925-1995) is a French philosopher and considered by many as one of the great thinkers of 20th century. His two-volume Capitalism and Schizophrenia (which he co-wrote with Felix Guattari) delivers insights into human nature and devastating critiques of capitalism. As part of a course on post-modernism and Buddhism he gave at the Graduate Theological Union in Spring 2008, dharmas blogger Doug Powers introduced the major theses of Deleuze and led a discussion on the intersections of Deleuzian and Buddhist concepts. In the coming weeks we will publish edited transcripts from these lectures on the university’s website. Here is a short preview:

“Both the Shurangama Sutra and this text (“What is Philosophy?”) are primarily about the issue of adding certainty or concreteness to something that’s only provisional. Read More …

“If people wish to fully understand

All Buddhas of the three periods of time,

They should contemplate the nature of the dharma realm:

Everything is made from mind alone.”— Avatamsaka Sutra

My understanding of the above verse has evolved since I first read it as a teenager. I no longer read it as mainly a cosmological statement —the Buddha wasn’t refuting a “world out there” that exists independent of its experiencers (nor was he confirming its existence)— but one that points to the centrality of our mind in the equation, because it’s the only instrument we have to know anything at all.

… the mind is saddled with a set of limitations —lenses, perspectives, points of view, positions— that mediates and changes how we perceive and process information.

This instrument of ours (Yogacara Buddhist texts describe the mind as 8 consciousnesses, with 5 of them correspond to the senses of seeing, hearing, smelling, tasting, and touching) is saddled with a set of limitations —lenses, perspectives, points of view, positions— that mediates and changes how we perceive and process information. The last line of the verse indicates something much more active: each of our minds is constantly forming (and being formed by) a unique set of limitations, leading to unique sensual experiences of the “world without”.

Everyday experiences give us a glimpse into this active and creative process. To an errant tourist, a dense forest is a menacing force to be feared, but to an herbalist or anyone trained in nature survival skills, the same forest can be a safe haven with food and shelter everywhere. Read More …